What is the role of art in the face of ecological crisis? - Part one: Awareness and Action

- Sofia Pantsjoha

- Jul 30, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 30, 2025

Consistency usually brings comfort - but now, when news headlines are reliably reeling off stories about victims of the latest eco-disaster or how climate change is affecting the world’s food security in another unforeseen way - a bit of change would be welcome. At this point it seems to be a fact of life that the world is on fire and there’s not much we can do about it. It’s fading into a background misery that we either try to avoid thinking about, are desensitised to, or, for others still, spend an unhealthy amount of time agonising over. The art-world mirror reflects this cultural shift with exhibitions that explore our relationships to and within ‘nature’* having become another consistent feature of our time. Since 2019, cultural institutions have even begun “Declaring Emergency” in response to a rising awareness and demand for action against climate and environmental degradation. [1] As our culture shifts, what is the role of art in the face of the ongoing ecological crisis?

During the final year of my Art & Psychology BA, a rude awakening of eco-anxiety converged the previously unrelated silos of my degree. That isn’t to say I hadn’t previously worried about the climate crisis, but all of the loose threads finally connected and I feel like I finally saw the world around me - and couldn’t unsee it. After a dissertation on climate change and uncertainty, and a degree show reckoning with the divides between urban human and vegetal life, I’ve emerged from university with the same anxieties hoping to contribute to the fight in some meaningful way. I sometimes wonder whether I might be better off retraining as an ecologist, but then I’m reminded of the whole Tory cyber retrain scheme [2] and out of spite I’ve decided I am sticking with art (at least for now).

I joke but I genuinely believe art can lead to real change (the cynicism that comes in waves is yet to take me over completely) and the ‘eco-art’ movement could be the prime space for it. Ecological art, interchangeably dubbed eco-art, describes art that engages with the interdependencies of living and non-living systems of the planet. [3] Eco-art practitioners often draw from diverse areas of academia, science, activism, and Indigenous knowledge. In a world where protest and scientific inquiry are increasingly stifled, this kind of interdisciplinary work is key. [4] It is also precisely the -art element of eco-art that enables it to cut through the constant ‘environmental warnings, policies and campaigns’ the majority are numb to, and re-ignite urgency. [5] However, as the eco-art scene grows, care must be taken to ensure it goes beyond the passive aesthetic appreciation of ‘nature’ previously lauded in landscape paintings.

‘True’ eco-art must therefore have an intersectional approach.

Simply ‘raising awareness’ of pollution or deforestation or plastic accumulation or animal exploitation or whatever eco-theme you choose is now not enough. Eco-art must go a step further and challenge the Western, extractivist, and anthropocentric systems of power and inequality, through “ecological, social, cultural, political or economic dimensions”. This inherently means that it must be radical, and adhere to an ethics beyond what we know: either creating alternative ways of being, reigniting forgotten sensibilities or at least providing the space for such things to happen.

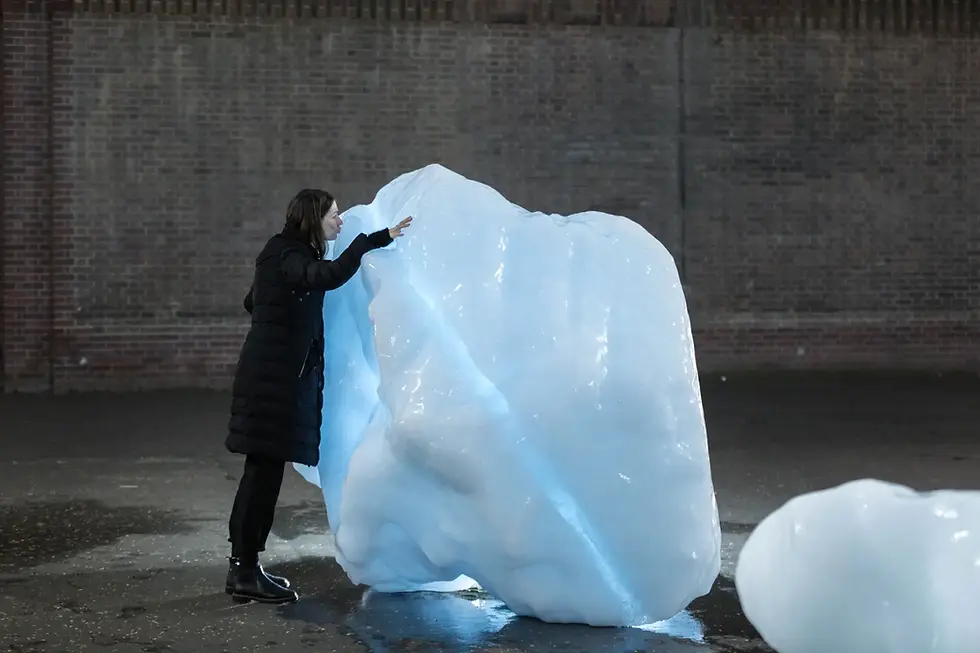

Olafur Eliasson’s Ice Watch (2014), an installation of blocks of glacial ice displayed in urban settings, perhaps does the opposite. Whilst, arguably, it provided an urgent visual to a far-away disaster, it only served to promote the idea that the impacts of climate change are indeed far away and not yet encroaching on our ways of life (and therefore beyond our control). Viewers may have been struck by the beautiful tragedy before them, but it failed to draw connections between “local activities [and] global formations”, as if afraid to confront individuals with their own complicity. [6] The work doesn’t suggest an alternative, or appear to criticise anything in particular - the kind of awareness it produces is simply a passive doom.

An artwork that activated me, ‘Wheatfield - A Confrontation’ by Agnes Denes might make any eco-artists reading this roll their eyes at its predictability. But personally, discovering the work contributed to my own eco-consciousness, prompting me to critically examine my own surroundings. I began questioning land use and ownership, human distinctions between useful/useless vegetal life, the decline of fundamental human skills in the neoliberal era, our growing exploitation of the global periphery, and the movement of products and people. I recognised how these factors intertwine to perpetuate a system that prioritizes the profits of a few at the expense of many, ultimately leading to ecological destruction. These intended meanings behind the artwork have been eroded by our culture of green-washing. Amber Husain writes on this issue in You’re Missing the Point of Agnes Denes’s ‘Wheatfield’ which confronts how viewers and critics have reduced the piece to an aesthetic of rural idyll, failing to recognise the radical nature of the work. The 2.2 acre field of wheat (grown on a plot of land costing $4.5 billion by the World Trade Center) was not a mere act of contrasting the urban with the rural, but temporarily reclaimed ownership over this land to criticise the absurdity of capitalist priorities and careless environmental exploitation. Over 1000lbs of wheat was harvested and distributed across the world during 'The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger’. Instead, gentrifiers with eco-capitalist agendas have co-opted the aesthetics of 'Wheatfield…' to boost property values, displacing lower-income communities in the process.

Wheatfield isn’t perfect: there’s some irony in producing a monoculture to critique profit-seeking, and to combat hunger, and perhaps that’s why the wider meaning is lost on some (although that’s being hopeful). But after all, it highlights and experiments with the typically unseen interdependencies between living things and their environments, considering the overlooked social, political and economic structures in our day-to-day lives. In some way, it also “strives to shape [...] common spaces for wider communities to explore and change situations”[7] and doesn’t act in isolation. Socially engaged eco-art has the power to foster hope and offer alternatives through community action. But changes must be made in our own everyday lives, not just in these widescale demonstrations. It is ultimately the insidious Western ideologies of patriarchy, progress, expansion, our greed for constant novelty and immediacy that underlie coloniality and eco-injustices. Art must shift the underlying ethics of Western societies

Exchange Values on the Table (1996 - ongoing) by Shelley Sacks invites people to consider their own positioning in the global trade, as consumer, artist, producer. The project began with Sacks collecting banana skins and tracing them back to those who grew them, asking the growers to share their experiences of the trade. This act transforms an everyday object, the banana, into a tool with which people can examine the interconnected systems that led to it rotting on a shelf in the supermarket. Exchange Value is a social sculpture that has evolved over time, sometimes inviting people in from the street to eat a banana and engaging them in a discussion about fair trade, monocultural farming, environmental racism, and racial capitalism. [8] At other times bringing together diverse groups of people; activists, economists, government officials, artists (etc) to recognise their own power as consumers and discuss new modes of being in the world. This participatory element of the piece allows for individuals to embark on their own transformation; raising an active awareness in a way that facilitates eco-consciousness. While some may question the direct impact of the work as it doesn't exactly halt the corporate power or over-use of agrochemicals that dominates the banana industry. However, the act of engaging in communal, critical conversations is a crucial step towards slowing down and fostering active participation from those further down the supply chain - those who have power to hold others accountable via their consumer habits.

DIY Algae/Hydrogen Kit (2004) by Amy Franceschini and Jonathan Meuser is perhaps a more direct example of action through eco-art. This collaborative piece combined the science of decentralised energy production with the situation of the art space in order to disseminate an eco-friendly alternative to fossil fuels (using algae). [9] Franceschini’s DIY approach to the kit and zine facilitated wider participation beyond the typical scientific audience, pointing to the site of an artwork as a key element of its influence. Whether or not the gallery visitors actually replicated these experiments at home remains irrelevant, as the shifts in awareness and accountability are what hold true value. Whilst striving for such direct action may seem the most valuable, constant progress and productivity are what landed us here: the answers to the poly-crisis lie in an urgent process of slowing down and re-examining. [10]

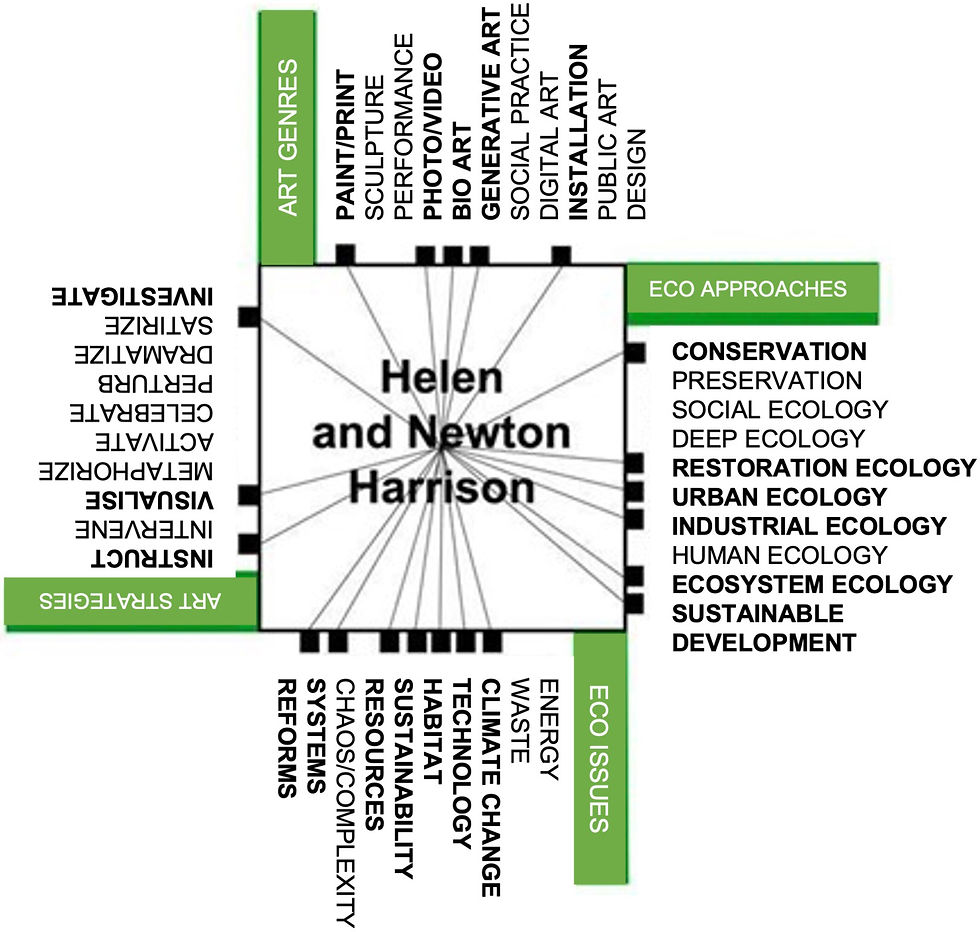

It’s been a whole 6 years since Culture Declared Emergency in the UK (a phenomenon that has since spread across the globe) and some of the ‘declarers’ have their Net Zero goals set for 2040. Sure, the art world isn't a leading producer of fossil fuels but I worry that institutional adoption of phrases like ‘declaring emergency’ is simply diluting a movement that requires urgent radicalism. People grow accustomed to aesthetics and language: urban greenery, emergencies and declarations risk fading into the background noise. In a time of ecological crisis (after crisis after crisis), we need eco-art to disrupt passive awareness and draw out active participation; to build community and foster collaboration across disciplines, but operate beyond their rigid boundaries. There is an endless combination of methods, eco-considerations, and mediums at our disposal, [see below] but in extractive consumer cultures, we must ensure we use them to actually subvert our current ways of being - instead of painting ourselves green but upholding the same ideas that got us here in the first place.

[1] https://www.culturedeclares.org/

*We’ll get into that construct soon enough.

[3] T. J. Demos, Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology (MIT Press, 2016).

[5] Linda Weintraub, To Life!: Eco Art in Pursuit of a Sustainable Planet (Univ of California Press, 2012), p xiii.

[6] Demos, Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology, p 12.

[7] Sacha Kagan, Toward Global (Environ)Mental Change: Transformative Art and Cultures of Sustainability, 2012, p 19.

[9] Weintraub, To Life!: Eco Art in Pursuit of a Sustainable Planet, pp 171-175.

[10] Timothy Morton, Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Harvard University Press, 2009).

References & further reading

Culture Declares Emergency https://www.culturedeclares.org/

Black, J. E., K. Morrison, J. Urquhart, C. Potter, P. Courtney, and A. Goodenough. “Bringing the Arts Into Socio‐ecological Research: An Analysis of the Barriers and Opportunities to Collaboration Across the Divide.” People and Nature 5, no. 4 (June 13, 2023): 1135–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10489.

Demos, T. J. Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology. MIT Press, 2016.

Husain, Amber. “You’re Missing The Point of Agnes Denes’s ‘Wheatfield.’” ArtReview, March 5, 2025. https://artreview.com/youre-missing-the-point-of-agnes-denes-wheatfield-feature-amber-husain/.

Kagan, S. and Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (2012). Toward global (environ)mental change transformative art and cultures of sustainability. Berlin Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Morton, Timothy. Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics. Harvard University Press, 2009.

Sacks, S. Exchange Values on the Table, formerly known as 'Exchange Values: Images of Invisible Lives' is a social sculpture developed by Shelley Sacks in collaboration with banana producers in the Windward Islands. (1996 ongoing) https://exchange-values.org/

Weintraub, L. (2012). To life! : eco art in pursuit of a sustainable planet. Berkeley: University Of California Press.

Comments